The two men who could bring down college basketball

The two men who could control the fate of college basketball combine for nearly 40 years of experience in the sneaker industry, prominent executives who kept intentionally low profiles. One is the son of a retired judge, and the other the son of a legendary New York City high school coach. Both are married, fathers and had clean-cut reputations that belie the federal charges of wire fraud conspiracy, wire fraud and money laundering conspiracy that have them each facing a maximum 80 years in prison.

Adidas executives Merl Code and Jim Gatto were widely known in the basketball industry as benevolent dealmakers, behind-the-scenes shakers and confidants of the sport’s boldfaced names. Until this week, they were largely anonymous outside the tight-knit basketball scene. That changed when Code and Gatto became two of the 10 basketball industry figures arrested in a federal probe that’s shaken the sport to its core. Legal experts predict they’ll be of particular interest of federal investigators trying to unwind the complicated financial web around college basketball that’s led to charges that include bribery and conspiracy.

“In a white-collar investigation, the executives at any company, including the shoe companies, are going to be the top targets,” said Stephen L. Hill Jr., a partner at Dentons in Kansas City and former U.S. Attorney who prosecuted the Myron Piggie case. “To get credit for cooperation, they’re going to have to provide something of value to figuring out the scheme and who was involved. Based on the complaints, the government would be interested in coaches, players, administration officials and other executives at their company.”

That potentially leaves Gatto and Code with decisions that could significantly alter the landscape of the sport. Of the 10 figures in the basketball industry, none figure to have more wide-ranging information of the inner-workings of the black market of agents, shoe companies, financial advisers and college basketball recruiting than Code and Gatto.

Code, 43, worked at Nike for more than a decade before going to Adidas in 2015. At Nike he rose to a powerful position atop the company’s signature Elite Youth Basketball League grassroots program, which annually showcases the country’s top high school prospects. Gatto, 47, worked at Adidas for 24 years after landing with the company, in part, thanks to his father’s connections. Both have worked closely with most of the country’s high-profile coaches, which has created an undercurrent of uncertainty around the sport.

“The coaches who’ve dealt with the sneaker companies are sweating bullets and having sleepless nights,” said Fran Fraschilla, an ESPN analyst who coached at St. John’s and New Mexico. “If I’m Jim Gatto and Merl Code, I like some of these coaches, but I love my family more.”

And that leaves a series of compelling questions: Who are the two executives thrust from obscurity that could hold the future of the sport in their hands? And could their knowledge of the basketball scene lead to more firings, charges and chaos?

*****

Jim Gatto lives in a home valued at more than a half-million dollars in tony Wilsonville, Oregon, replete with a stone arch at the front door. It’s a long way from his blue-collar New York upbringing, as his father, also known as Jim Gatto, worked as an usher at New York Mets games to supplement his income. Gatto Sr. is the archetype of the throwback New York City coaches from the past generation, winning more than 500 games at St. John’s Prep in Queens and getting elected into the Catholic High School Athletic Association Hall of Fame. His career began in 1970, when the school was known as Mater Christi, and lasted long enough that he coached Taliek Brown, who won a national title as UConn’s point guard in 2004.

The elder Gatto’s coaching success led to his son’s career path, as Gatto Sr. coached in the Roundball Classic, a high school all-star game that helped launch the career of long-time sneaker executive Sonny Vaccaro. As Vaccaro recalls, Gatto Sr. called him for a favor to hire his son at an entry-level position. Gatto blossomed at Adidas, traveling the world with Kobe Bryant, befriending Kansas’ Bill Self and Mississippi State’s Ben Howland and even participating in an ill-fated task force to try clean up basketball. In nearly a quarter-century at Adidas, he rose to become the Director of Global Sports Marketing.

“He came from being in the mail room,” Vaccaro said, “to running William Morris.”

One relationship that may end up under scrutiny is Gatto’s friendship with NBA agent Andy Miller, a close ally in his rise through the profession. Miller’s office was reportedly raided by the feds soon after the announcement of the 10 arrests on Tuesday. (Multiple Miller clients ended up with Adidas contracts over the years, including hallmark clients Kevin Garnett, Chauncey Billups and Kristaps Porzingis.)

Those who know Gatto well are stunned by his arrest and the potentially precarious position of what information he could offer authorities. They knew Gatto navigated in the gray underworld of grassroots basketball, but his reputation was more as an affable and shrewd businessman than a street hustler. Vaccaro said if he’d been called about Gatto last week, he’d have described him as an “altar boy.” Added Fraschilla: “It’s incomprehensible that the Jim Gatto I know is stuck in the middle of this. Knowing the shoe/agent/recruiting business how I know it, he got sucked in. He got sucked into a world he wasn’t accustomed to.”

Gatto is married and has two children, 12 and 16. Facing up to 80 years of prison time, the question lingers as to whether he’ll cooperate with the federal government as it continues its investigation. “The isn’t ‘The Wire,'” said a grassroots basketball official who has known Gatto for years. “Jim Gatto is a businessman. The thought of going to jail is an abstract idea.”

*****

Any mention of Code to those who’ve known him during his tenure at Nike and Adidas over the years usually references his father almost immediately. Merl F. Code is a staple of the Greenville, South Carolina, political and philanthropic scene, having served as a judge, lawyer and on more than a dozen community boards. Merl Code’s grandfather played baseball in the Negro Leagues in the 1930s and 1940s.

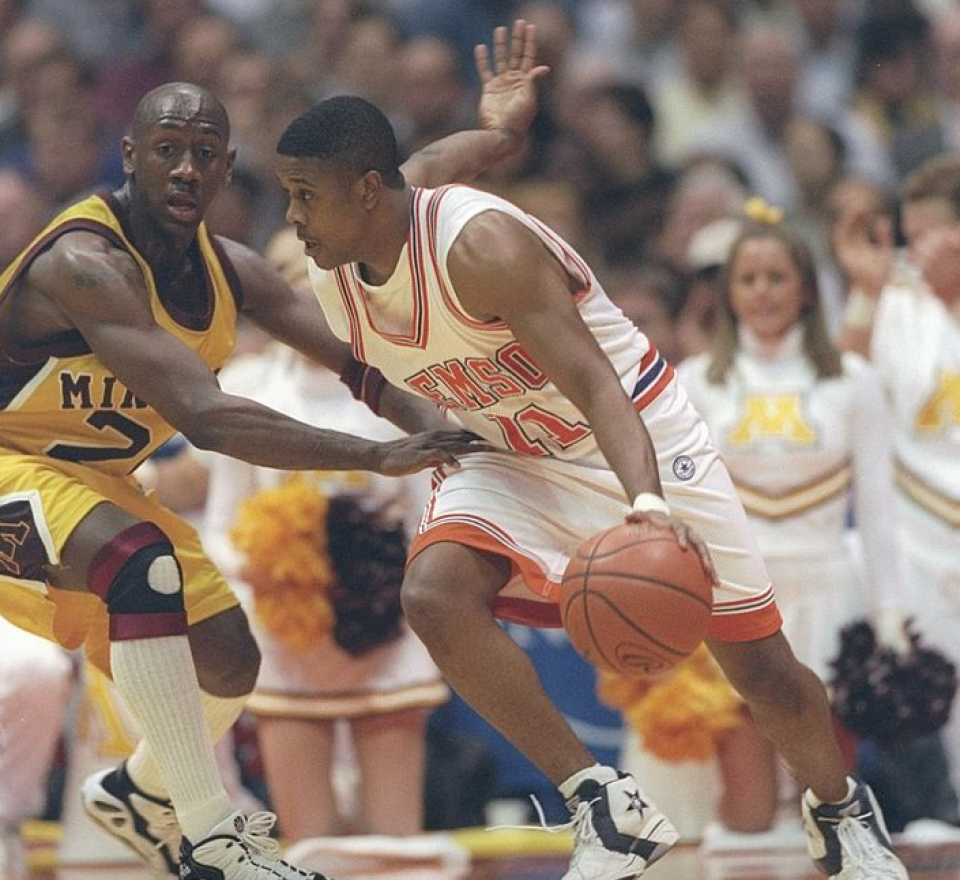

“There’s not a more respected family in the state of South Carolina than the Code family,” said Tennessee coach Rick Barnes, who coached Merl Code at Clemson in the mid-1990s. “I’m sure they are crushed right now.”

Merl Code graduated from Clemson and got a tryout with the Denver Nuggets in 1997. He bounced around the basketball world before landing with Nike, as his first publicized job with them came in 2003. Code began servicing Nike athletes in the Midwest, getting to know the professional side of the business. He eventually worked his way up the ranks of the grassroots, running Nike’s Skills Academies, top camps and finally the prestigious EYBL.

“He was in charge of the budgets, picking the teams and the relationships with the college coaches,” said a person familiar with Code. “He ran everything and nothing happened without him knowing. That’s why most people are scared.”

What gives a person like Code so much power is key to understanding the complexity of this case. Code ultimately oversaw what teams got invited to Nike’s top events, players selected to all-star games and allotting money to the high-profile AAU teams. His relationships and intimate familiarity with players and their ecosystems helped ingratiate him with high-profile Nike schools like Kentucky, Duke and Arizona.

“His job was to go out and get the best talent,” said Corey Evans, a recruiting analyst for Rivals.com. “He was the connector between agents and players, college programs and players and college programs and agents. He’s the ultimate middle-man.”

Code kept a defiantly low profile in his high-powered position, as his name didn’t appear publicly affiliated with Nike from 2005-12, according to a LexisNexis search. When this reporter approached Code to introduce himself at a Nike AAU event in 2012, Code declined to talk. (Code is married, lives in South Carolina and has a young son from a prior relationship who lives in Houston.)

Code’s firing from Nike received little publicity, as did his hiring by Adidas in 2015. Code’s departure is regarded around the industry as contentious, as he finds himself in an uncomfortable spotlight.

“It was not the cleanest of breakups,” Evans said. “Whenever he gets talking, he may get talking. Nike guys are really nervous about this. They’re nervous about [what] Merl Code may have to say [about] his prior establishment.”

The variety of top programs, agents and players he’s worked with make Code a prime potential federal witness.

“He may be more valuable than Gatto in a way,” said Carl Tobias, a law professor at the University of Richmond. “He has two of the biggest players and information on them. He’s seen them both from the inside.”

*****If this whole investigation ever gets made into a movie, the dialogue between Code and Gatto can be taken directly from the wiretaps to the big screen. They seem to be auditioning for this generation’s “Blue Chips,” as they discuss, in various conversations, bidding for players and schemes to launder money.

Code: “You guys are being introduced to … how stuff happens with kids and getting into particular schools and so this is kind of one of those instances where we needed to step up and help one of our flagship schools in [Louisville].”

In another conversation:

Gatto: “Try and get it to what we did with [Brian Bowen], a [$100,000].”

Code:” [I’m not sure] they’ll take that much less, but if I can take it down at least twenty five.”

And another:

Code: Requesting a payment made in cash for “for cleanliness and lack of questions.”

And so the question lingers on: Just how much damage, both in terms of legalities and NCAA rules, could an honest assessment of the landscape from both Gatto and Code bring? The way they talk in the federal documents, these do not sound like the first deals they’ve brokered.

In a searing scandal that’s pierced the soul of the sport of college basketball, Code and Gatto have the potential to provide information that can upend the establishment. There’s likely no major program they haven’t had exposure to or could deliver information about.

“I think the dominoes will fall incredibly quickly,” said a Power Five athletic director, who asked to remain anonymous. “I think some people with all the information have already flipped or will flip. Then it’s relatively easy.”

At least one of the assistant coaches charged is adamant he will not cooperate with authorities, a source with knowledge of his legal strategy told Yahoo Sports. But sleeping has still been a challenge for head coaches and assistants around the country. Two of the basketball industry’s consummate insiders are facing a maximum of a combined 160 years in prison. The realistic sentencing targets for Gatto and Code aren’t known. Prosecutors say that both having money-laundering charges, which typically comes with stiff penalties, is a big leverage chip for the feds.

The answer on whether to provide the federal government a more detailed playbook about the inner-workings of the sport appears obvious.

“If I get an opportunity to get a more lenient sentence in order to tell what I know, I’m going to do it,” Fraschilla said. “We’re not talking about bringing down the mob or starting a war with North Korea. We’re talking about college basketball.”

More from Yahoo Sports:

• Report: NBA issues memo on anthem protests

• Police footage of NFL star’s detainment released

• Warriors will pay for parade — but not happily